In this guest blog, Professor Kate Loveman, author of The Strange History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary (2025), introduces Samuel Pepys, his shorthand diary, and efforts to decipher it.

Who was Samuel Pepys and how did he use shorthand?

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was a naval administrator who worked in London during the late seventeenth century. He kept extensive records of his life and his work at the navy, many of them in shorthand.

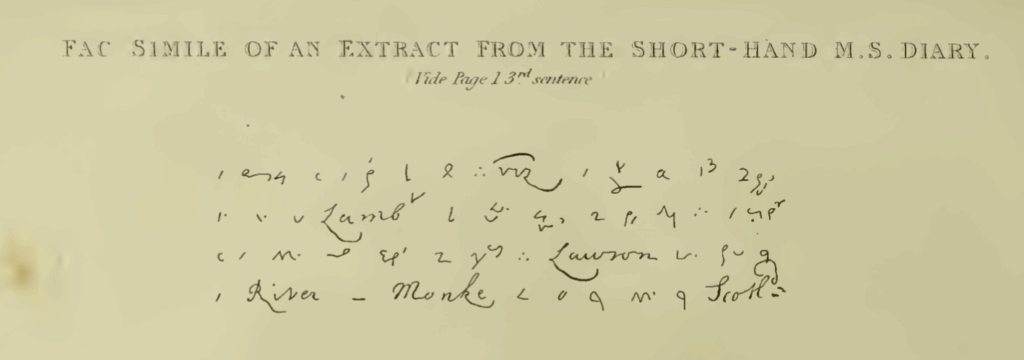

He’s most famous for keeping a shorthand diary which describes major events of the 1660s, such as the plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London. Pepys also recorded a lot of court scandal and much about his personal life (including obscene material judged unprintable until the 1970s). For him, one of the main advantages of using shorthand was that it prevented his diary from being easily read. His journal is now the most vivid account we have of life in 1660s London.

What is Pepys’s shorthand like?

He used one of the most popular systems of his day. It was called ‘Tachygraphy’ (or ‘short-writing’) and had been devised by Thomas Shelton. It has symbols for letters, common beginnings and endings of words, and for common words. As it’s really designed for taking notes from sermons or religious texts, a lot of those ‘common’ words are terms like ‘baptism’, ‘chastisement’ and ‘righteous’. Pepys was less interested in the system’s religious uses, but he was an expert shorthand writer. His writing is usually pretty clear, rather than of the scribbled ‘notes to self’ kind.

What are the challenges of ‘decoding’ Pepys’s shorthand? Can you tell us more about previous attempts?

Shelton’s system can be tricky to read because of close similarities between symbols, and because it represents vowels using some very fine distinctions in positions of symbols. Users are also encouraged to cut out ‘superfluous’ letters and to spell phonetically. When you bear in mind that Pepys was spelling in seventeenth-century ways (which are already various), it can get complicated! Pepys also developed additional methods for further disguising sexual passages, including switching languages. These can be fiendish to unpick.

However, the main problem for the editors who first published Pepys’s diary in 1825 was that, by that time, Pepys’s seventeenth-century shorthand wasn’t readily recognised as Shelton’s. They began by trying to crack it from scratch. The first person to transcribe all of the diary, a student called John Smith in the 1820s, did in fact, identify Shelton’s method, but he kept that knowledge quiet. Very few people over the last two hundred years have been able to read Shelton’s system and most of the people down the centuries who have edited Pepys’s diary could not actually read his shorthand – they relied on others to transcribe it.

How can I find out more?

To celebrate the 200th anniversary of the diary’s publication, I’m running a free online shorthand workshop in early July.

This will introduce the basics of Shelton’s system and there’ll be a chance to have a go at working out some short phrases using images from Pepys’s diary that are rarely seen. No prior knowledge of Pepys or of seventeenth-century shorthand is required!

You can register via Eventbrite. Sign up here for the event on Saturday 5th July, 6-7pm BST Or, alternatively, register here for Tuesday 8 July, 2-3pm BST.